Robotics in prosthetics

Technology has advanced,

giving amputees mobility and hope

By Melanie J. Rutt

Special to the Knightly News

According to The Amputee Coalition, a nonprofit support organization for amputees, about 500 people in the United States lose a limb every day, which adds up to 185,000 amputations a year.

The Coalition says that number will rise to 3.6 million people living with limb loss by 2050.

Most amputations involve a leg or part of one, and the growing majority of people who will have an amputation are between the ages of 45 and 85. In addition to the medical team that takes care of them initially, these amputees will also be working closely with a prosthetist and physical therapy team to help them recover and regain as much mobility as possible.

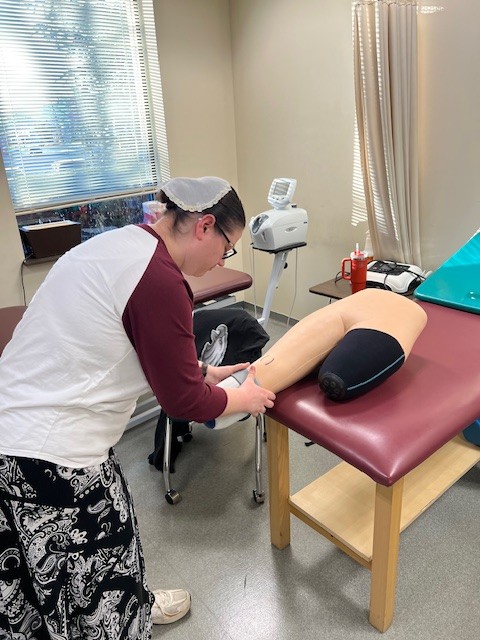

At Central Penn, the Physical Therapist Assistant (PTA) program has been teaching students the skills needed to help patients with an amputation to heal and learn to use a prosthesis.

Visit from a robotics expert

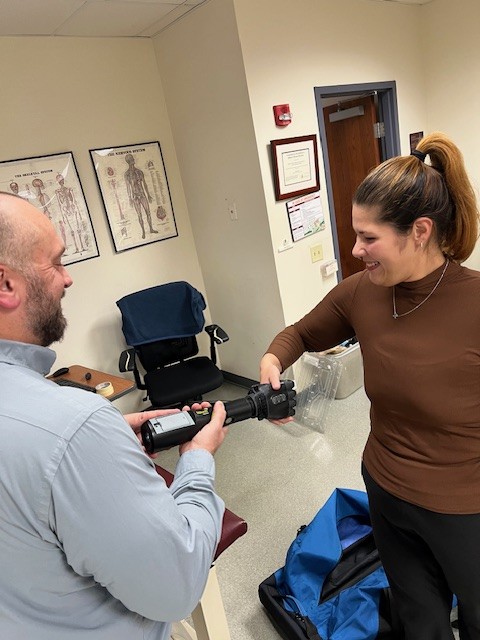

Photo by Taylor Lentz

Jason Kunec, a prosthetist and orthotist who is also a regional manager with Regional Clinical Manager at Ability OttoBock.care, came to a PTA procedures class in the fall term to talk about different parts of a prosthesis and how different levels of technology are available to people who need that technology.

Kunec showed the students in the class, taught by Professor Taylor Lentz, sockets, how to move the fingers of a robotic hand and allowed students to practice putting various suspension material—a variety of mean of helping a prosthesis stay in place and move properly— on amputee manikins used in the class. Students also experienced what it might feel like to walk with prostheses by strapping them into walking boots attached to prosthetic feet.

Kunec said that to qualify for higher-level technology, a patient must be able to prove a need for it and have high-enough cognitive ability and mobility to use it. The mobility, known as “K levels” (K for knee), runs from zero to four. Insurance companies use the levels to determine which prostheses they are willing to provide for a patient.

Prostheses are not cheap. They cost from about $3,000 to over $70,000. Kunec said he has seen prostheses that cost over $100,000. The more advanced the technology used in a prosthesis is, the more expensive it will be, and the harder it will be to convince insurance companies to cover it.

Patients at the K0 level will be using a wheelchair for all their mobility anyplace.

People with levels K1 and K2 use basic prostheses that provide limited mobility, primarily at home, and they use wheelchairs outside their home.

People with K3-level mobility use their prostheses all day for all their mobility, and prostheses for K4 level ability are reserved for athletic adults and children.

Where the technology goes

Most of the more advanced features of a prosthetic are in the knee, ankle, foot and hand. Prosthetic knees, for example, can be mechanical or powered. Mechanical knees have a component that can be locked and unlocked by how the user places weight on the foot and how hips are flexed when walking. Powered knees use computers to detect how fast a person is walking and whether the person is going up stairs, in which case the computer adjusts for how the motor bends the knee as needed for the person. Powered knees are intended more to increase the mobility of people who have lost legs.

An option that combines mechanics and computers called the microprocessor knee is available. Instead of bending the knee for a person, the computer in the microprocessor knee detects the user’s walking pattern and applies the right amount of resistance for smoother walking.

As with the knee, prosthetic ankles and feet come in varying levels of stability provided. Ankle components can be solid with no movement, have one axis and allow the foot to move only up and down, or they can be multi-axial and allow the foot to move from side to side and up and down. The most basic foot is super-stable and can be solid wood or plastic, with no movement, or it can be what’s called a flexible keel, which allows the toes part of the foot to bend a little for a more natural feel.

A step up are the dynamic response feet, which are less stable but have more of a spring effect that returns energy to the person walking, and makes walking and running less tiring. While there are different types, one type runners use that people may have seen is a prosthetic that looks like a C-shaped blade.

Photo by Taylor Lentz

Fairly new to the scene is the microprocessor foot, which, like the knee, uses computers and sensors to detect the user’s walking speed and then applies the right amount of resistance, mimicking the motion of a human foot.

The human hand’s fine-motor skills are so advanced that the search for the most useful competent prosthesis continues. Engineers are working on a better solution than those available and there are quite a few clinical trial papers researchers have published about prostheses. The most basic prosthetic hand is one that straps onto an amputee’s shoulder and is maneuvered by the user moving shoulder muscles.

Other applications of prosthesis technology

Breakthroughs are being made by connecting sensors implanted in amputated arms to forward the signals from the brain to computers inside the hand to move it. A study by Case Western Reserve University showed that not only were signals from the brain received by a processor in the prosthesis, but the signals were returned to the brain, causing the user to “feel” the prosthesis.

As wonderful and exciting as these new technological discoveries are, most people will probably never have access to them because of the devices’ cost, Kunec explained. He added that even people who qualify for higher-tech prostheses often prefer a more basic model for everyday life. He mentioned one person with an above-knee amputation who was a plumber. He ended up getting a second, more basic prosthesis, and wears his fancy prosthesis to church. One reason people may prefer the basic model for work is that more advanced prostheses are heavier, have more places for things to go wrong and require much more maintenance.

Advances in prostheses are helping to show amputees there’s hope for the future, and that they can achieve goals they might have thought they could not.

Comment or story idea? Contact [email protected].

Edited by media-club co-adviser and this blog’s editor, Professor Michael Lear-Olimpi.